Creation out of Catastrophe: Freud’s Kabbalah

One way of historicizing the psychoanalytic project is as a form of secular Kabbalah; that is, as the practice of Kabbalah stripped of transcendence; a Kabbalah without God (a non-Kabbalah, to use the parlance of Laruelle). Freud’s great mystical insight is that the other world told of by the mystics is less transcendent than radically immanent; rather more intimate and more real than we can ever know or understand, and yet one that unilaterally determines the psyche in the last instance. In my view he borrowed this other world directly from Kabbalah. In Freud, of course, the other world is the world of the other.

A growing body of literature has been tracing the historical relation between Kabbalah and psychoanalysis. While Freud could be rather discrete regarding his Jewish identity, and, as far as I know, never cites Kabbalah by name, it is becoming increasingly apparent that he knew a great deal about both the Torah and the Kabbalah as practiced in the Hasidic communities of Mitteleuropa in and around where he grew up; his father came from an Hasidic family after all. The further implications are that he not only knew a great deal about the Jewish mysticism, but was also influenced by it. This growing scholarship claims that everything that is magical and strange in psychoanalysis, every unexpected reversal and spatial inversion, all the inverted worlds, and every hidden truth, finds its origin in the millennia spanning tradition of Kabbalah. So much so that the Hegelian dialectics that Lacan and Zizek read into Freud amount to a kind of white-washing of this most esoteric of Jewish mystical practices. Is not dialectics just a cheap Teutonic hermeticism?

Borges once gave an extemporaneous lecture on the Kabbalah and declared that he hardly had the right to speak of such matters. I am no less an imposter. Nevertheless the strange connections between my chosen profession and these arcane techniques are too profound to pass without mention.

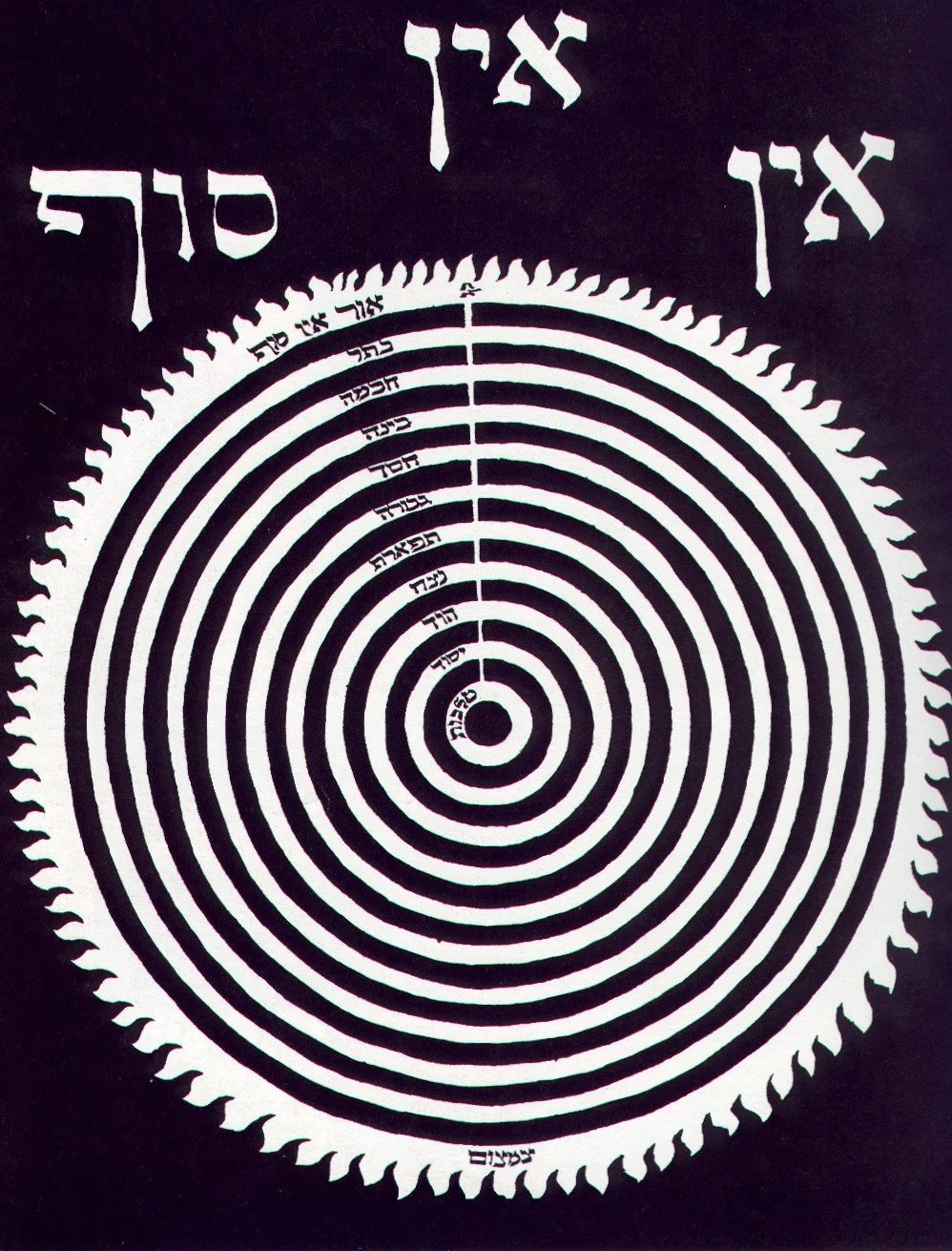

The Ein Sof

A Rough Outline of the Kabbalistic Cosmos…

In the beginning only god existed, the Ein Sof, the unthinkable godhead. God created from nothing—Ayin—the torah says and the Kabbalists take this literally so that the Ein Sof godhead is itself a void and pure nothingness even while being the absolute plenary source of all creation; it’s the extreme form of the apophatic god of negative theology, remaining totally indifferent and prior to any representation whatsoever.

But the godhead was lonely, or bored maybe, and so he created a void within himself, a womb the size of the universe and into this womb he places creation, which form a series of nested vessels; the zim zum. Into these vessels of creation he places the dude Adam Kadmon, who is meant to redeem the creation, (and by doing so redeeming God, who is kind of fucked up in that way), but Adam Kadmon neglects his duty by, instead, getting it on with Eve.

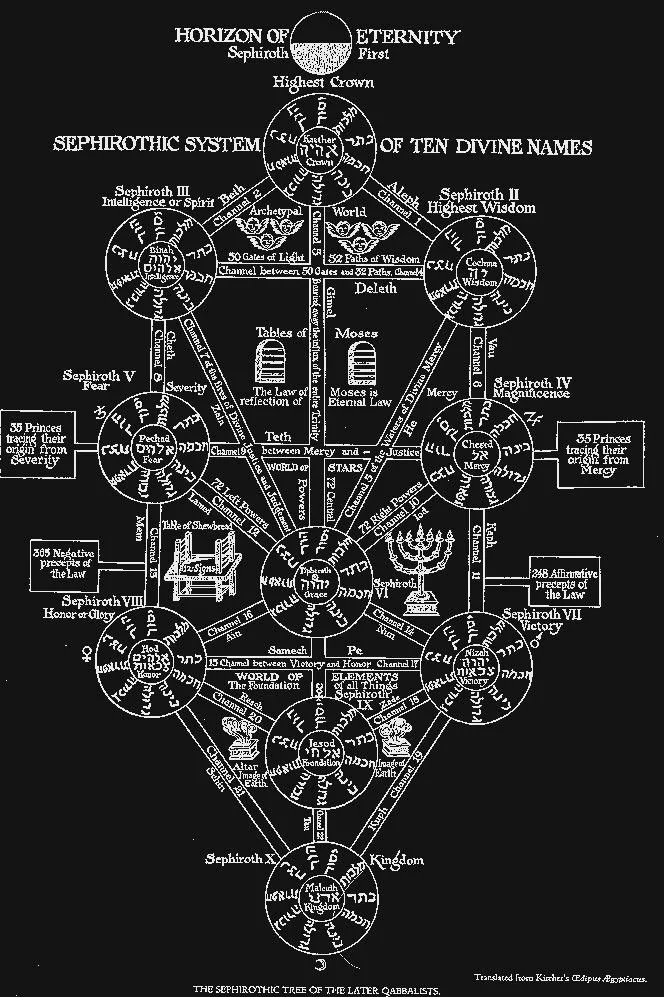

At this point all hell lets loose, which is not hell but rather the incinerating light of God that shatters the vessels and scatters shards of divinity all over the place and so it is now the destiny of the elected few—for example the Hasidic rabbis of Williamsburg—to collect the scattered divine sparks of the deity and so redeem the godhead’s manifestation upon earth. The godhead is continually emanating this incinerating light and it is only the pure of heart, who have studied torah for decades and have been ritually cleansed many times, who can withstand the rays of God and apprehend the worldly manifestations of the divine and unthinkable void as it appears in the guise of the saphires, or sefirot, each organized along the shape of the human body.

The Power of the Question

The historian notes that Kabbalah, in its written form, was developed as a direct response to exile, in particular when the Jews were banished from Christian Spain in the 15th century. That is, the Kabbalah is essentially a very complicated clandestine practice by which to study and process the nature of evil: or as the religious-studies nerds like to say, a theodicy. Eli Wiesel’s holocaust memoir Night (1956) is one such text, located within the Kabbalistic universe, exploring the divine paradox that it is only when God is most absent that he reveals his true presence.

“Every question possessed a power that was lost in its answer,” a Rabbi tells Elie Wiesel at the beginning of that book. I first encountered this idea from Elie Wiesel himself when I saw him speak in Vancouver BC in 2012, and I’ll confess that this statement has had a profound effect upon me to this day; it has become a kind of dharma. One could say that it forms the essential interrogative stance of both Kabbalah and psychoanalysis; an attempt to remain within the power of the question. The subtlety and nuance of Freud’s style resides within this tradition and that continues throughout the psychoanalytic literature. See for example the hem and haw style of Adam Philips as an example of this intentional undecidability.

Psychoanalysis as Non-Kabbalah

While a complete comparison between psychoanalysis and Kabbalah has filled a number of books, and no doubt will fill more, I will note here only a few points of interest, strong continuities between the disparate practices. Adam Philips has suggested recently that for any psychoanalyst Freud has no precursor; on the contrary, I argue that Freud’s preeminant precursors are the countless scribes of Jewish esoteric mystical practice.

1. As Without so Within: The peculiar structure of the subject, as laid out by psychoanalysis and Kabbalah, is one in which what is perceived in the exterior world is an emanation from your innermost interior. The self is a project of the world, the world is what the self projects. This curious structure, found in Melanie Klein no less than Lacan, is an hermetic structure that can probably be traced to the neoplatonists, if not far older. Kabbalah has adapted this structure, so that the world, as it is encountered by the mystical scholar, is laden with revelatory meaning, the radiating emanations from the other world.

Freud’s notion of endopsychic perception is the point where this inside=outside structure is made explicit in his new science of psychoanalysis. It is the perception of an unknowable psychical reality, cast outwards in the figurations of mythology, fantasy, belief, paranoid delusion and so on; in short, the full panoply of your own constellation of meaning is the reflection of a mystery emanating beyond categorical thought. This is summed up by the old hermetic saw, as above so below. Using this same esoteric formula Freud makes the cosmic local, reading into the metaphysics of the Kabbalah to extract metapsychology. The unconscious is the Ein Sof plenary/void, a seething cauldron, inaccessible to thought. The continual pressure of the drive is an emanation from the void; fantasy, dreams and parapraxes, repetition and negation are each the manifest figures of these latent emanations, the shards of an unthinkable reality. The void itself is not God, but rather the dark star of infantile amnesia pulsing within the maternal environment—that primordial unforgettable person.

2. Nachträglichkeit: The structure of as without so within, when placed into time, becomes nachträglichkeit; deferred action, or après coup: it is pure belatedness: what we are always waking up into. The common phrase from critical theory “always already” is the time of Kabbalah, the time of exile and the essence of the nachträglich; it is the situation that we find ourselves in, if we find ourselves at all. Awakening, if we ever do, to a catastrophe that has already happened. We wake up into a gloaming lit by unconscious fantasy. This is not the movement of dialectic but rather a unilateral determination. We are determined in the last instance by a dynamic force that remains inscrutable, that is foreclosed to thought; as Freud says, it is overdetermined.

Thinking, and by that I mean, any human thought whatsoever, is always late, not to mention reactionary.

3. The Linguistic Turn: But from out of the catastrophe proceeds all of creation. Kabbalah is a supreme idealism: the Hebrew alphabet precedes creation; words are more real than what they represent. When Freud speaks, regularly, of the “magic of words,” he may as well be speaking of a Talmudic magic. I first encountered the Kabbalah as it was refracted through the French post-structuralisms of Derrida, Levi-Strauss, and Lacan. Each of these in turn, of course, are refracted emanations from Freud in what has become known as the linguistic turn. But the Kabbalists made this turn long ago. If the Kabbalah is founded upon a sacred book, in Freud’s psychoanalysis the patient becomes this book. Latent and manifest meanings, esoteric and exoteric, are entangled in the speech of the patient, to be loosened and untied, interpreted by the Talmudic analysis of psyche. In this way The Interpretation of Dreams can be read as a complete manual for perceiving the emanations.

Freud is no idealist, but what he presents is a kind of local idealism. The word Kabbalah means received, or reception: we are all the receivers of an occult meaning that has inscribed us, from within and without, always already. Time and again Freud will describe how the use of language—the drives as our “mythology”—allows us to apprehend the truth of the other world that is our psychical reality. This is also a creative act. The magic of words is the power of creation, as when god spoke and the universe emerged out of nothing. This is still nachträglichkeit, but now in reverse: the future is made possible by speech. While we have all been inscribed by exile, in the last analysis we are each the arbiter of our own immanent revelation.

Neon Genesis Evangelion, 1995, Sefirot, Tree of life

“Certain mystical practices may succeed in upsetting the normal relations between the different regions of the mind, so that, for instance, perception may be able to grasp happenings in the depths of the ego and in the id which were otherwise inaccessible to it. It may safely be doubted, however, whether this road will lead us to the ultimate truths from which salvation is to be expected. Nevertheless it may be admitted that the therapeutic efforts of psycho-analysis have chosen a similar line of approach,” Freud, New Introductory Lectures, 1933.