In the Realm of Ether: on the work of Agnes Pelton

The Whitney hosted a retrospective of the artist Agnes Pelton in the spring and summer of 2020: Desert Transcendentalist. This is one of those rare shows, that, had I known about it, I would have traveled immediately, that afternoon, across town to go see it. At the time however I was either going crazy alone in my apartment, or out marching in the streets and, as with the rest of the world, I did not have the wherewithal to even begin to think about going to an art museum.

As such, I must be a troglodyte because I have only just encountered her work for the first time this last week. One of her paintings features on the cover of a recent book on Shamanism I am writing about. Intrigued by this book cover, I searched her work on the net and, images of her paintings populating my visual field, I had one of those most rare internet moments of beatitude and surprise; reader, I gasped.

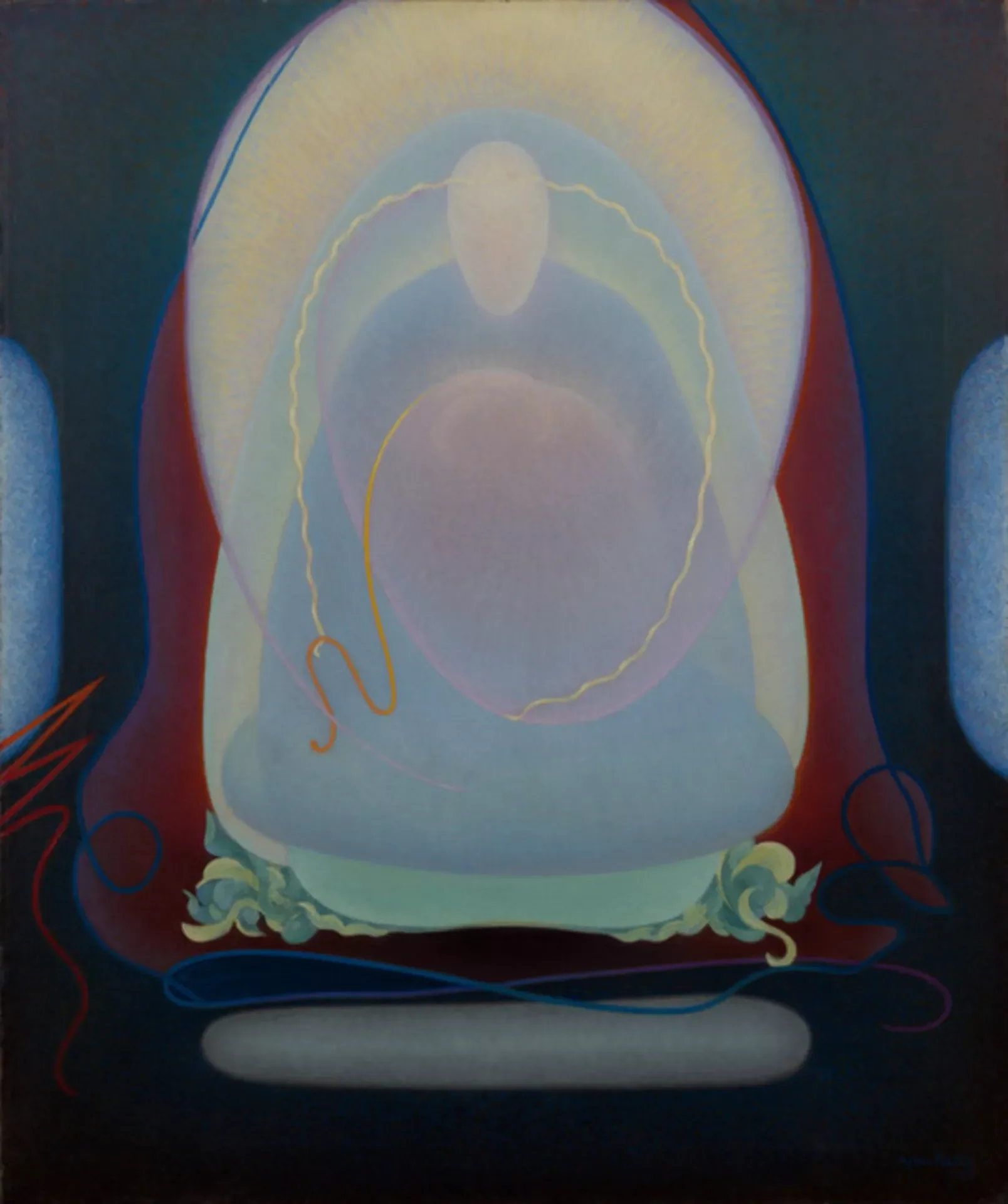

Feeling like a vision that has arrived from the future, its origins yet lie in a past indifferent to her work. American painter Agnes Pelton (1881-1961) is one of those untimely artists who, neglected in her own life, arrives 75 years after the fact with all of the powers of revelation. She revelates me at least. This work turns outward landscapes into inward terrain; what she called The Realm of Ether. Light beams from the paintings. There is a peculiar whimsy here, as if these were the landscapes of Looney Toons set in the fields of Elysium. Weirdly enough, these paintings resemble aspects of Hilma af Klint’s own visionary work but, due to af Klint’s self-imposed embargo, Agnes Pelton could not have known of her. So the paintings also resonate with a trans-planetary synchronicity, as if each artist were surfing on the winds of a shared alien world.

Three motifs present themselves: the desert, abstracted in the manner of Georgia O’Keefe, her near contemporary; the twisted vine, or loop de loop umbilical cord, typical of visionary art; and the cosmic egg—that body without organs—that is redolent of so much in mystical cosmogony. The paintings are mostly in portrait mode, so that, while they contain elements of landscape, they are not landscapes but rather, like af Klint’s work, they are themselves mystical experiences: the cosmic egg is also one’s own head, shining back to you from out of Ether. Work of this kind tends to complicate traditional theories of representation, for, like a Jasper Johns’ American flag painting that does not represent the flag, but rather is the flag in a very literal sense, these works are not representations of a visionary state, but rather the visionary state itself.