Tryptamine Style

It became apparent to me, while making my way back up to the surface after a medicine journey to the underworld, that the great power of visual art is that one does not have to think about it at all whatsoever. In that moment of coming back from a certain kind of psychosis, I found immediate relief and stability by staring at a Navajo style rug of zig-zag pattern and vibrant pink/red/orange colors. This rug was immediately captivating, and commanded or mesmerized perception-consciousness so that I could sit upright and begin to feel more like myself—in particular a self that likes the peyote style of the American South West.

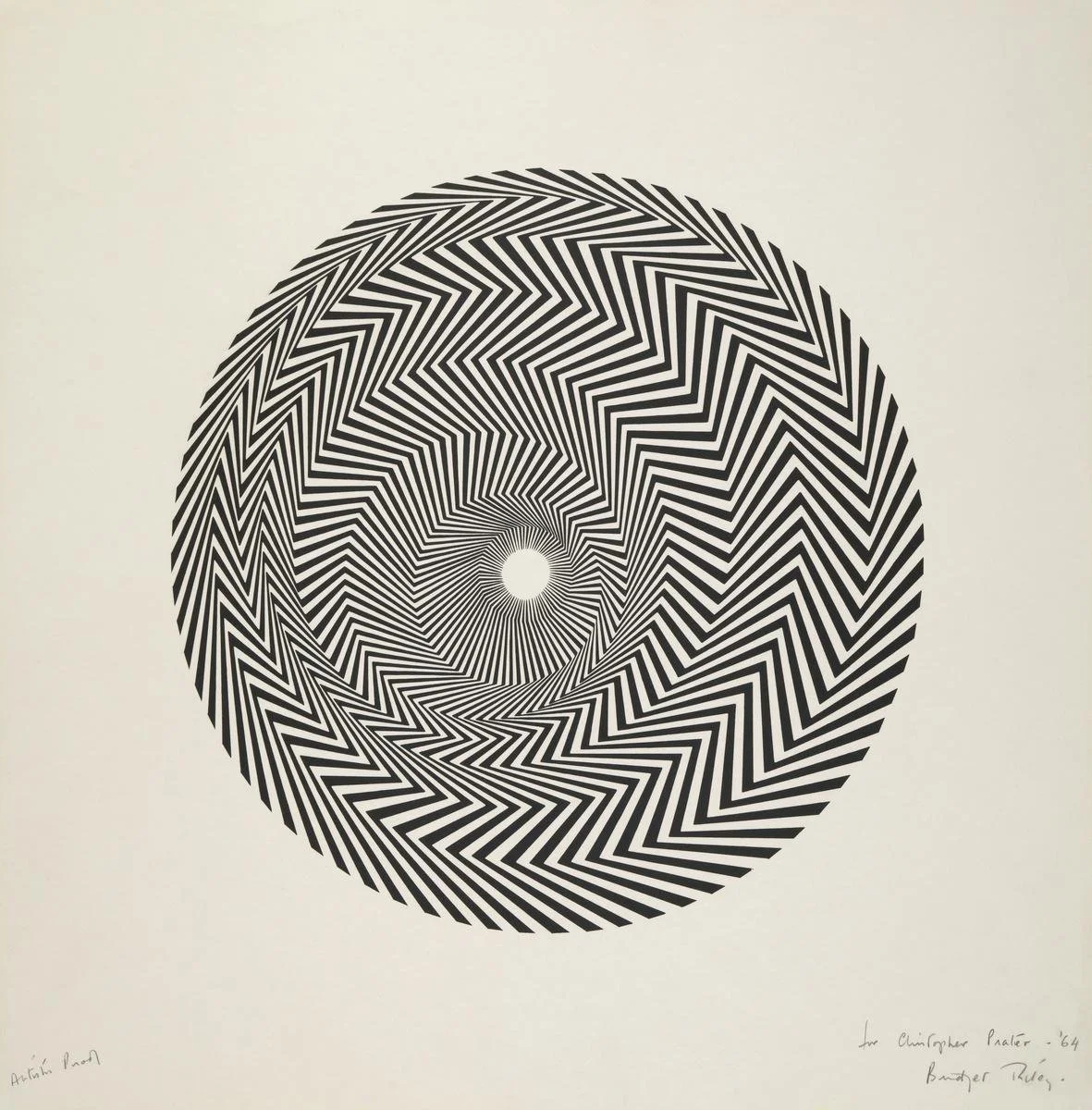

The genre of visual art known as Op-Art—or Optical Art—utilizes that same immediate visual power found in the Navejo style. This art is locally derived from minimalism, or is the same thing, and perhaps further derives from the greater movement of abstract expressionism. Its immediacy is no doubt due to its non-representational status—that is, you do not have to know anything to get it; its effect is there for all who have eyes to see. If the Prcpt-cs system is empty, then this kind of visual style fills or mesmerizes that system in an instant. Marcel Duchamp’s disparaging name for this was retinal art; he wanted art to be in the “service of the mind” and so he would make intentionally ugly work built upon elaborate conceptual scaffolding involving, for instance, a famous urinal—uh, urinal art?

By no means am I suggesting that you should turn off your mind when engaging art; rather I only wish note that an entire non-representational genre exists whose success is prior to—or indifferent to—the slipstream of the symbolic; while this art can engage the symbolic, it does not need to. I find a great deal of solace and even mental stability in this kind of mesmeric visual simplicity; it is a relief to not have to engage my mind. The captivating power of immediate aesthetic style might otherwise be a kind of the aesthetic defense. It is probably one of the earliest (and best) defenses we possess—if babies mesmerized by color and shape are any indication.

A further speculation would advance the notion that this optical style, in particular, is derived from an experience that remains outside of, or immanent to, the world of the everyday: that it is a style that comes from the other world (butthat resides in this one). It is a visual style that one encounters deep in certain psychedelic experiences: so much so that we might name it the Tryptamine Style. It is probably rather more basic (and more profound) than what we think of these days as psychedelic art, but someone who is more literate than I am in art history may begin to catalogue these alien motifs…

Untitled (Fragment 2), 1965, Bridget Riley

Turkish Mambo, 1967, Frank Stella

Blaze, 1964, Bridget Riley

Harran II, 1967, Frank Stella

Ganado Navejo Rug, 1920s, Unknown

Infinite Regress CXLIX, 2021, Eamon Ore Giron