The Arc of No Return: Helplessness and Overwhelm at the Movies

Vision of the Mortal Earth

Earthrise, hailed as the greatest environmental photograph of all time, and one of the more famous photographs of the era, was shot from lunar orbit on the Apollo 8 mission on Christmas Eve, 1968. The image of the small bright blue marble rising above the cold lunar landscape and hanging in the black void of space, brought us face to face with our own finitude and inspired a whole ecological movement. The emptiness of the cosmos became existential in an instant, a giant void to highlight the absurdity of our existence upon the mortal earth.

We might credit the astronauts with a certain amount of originality except that the image had already appeared earlier that year at the cineplex, in the opening sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) scored by the thundering drums of Sunrise, from Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra (1896). In the sequence, the sun rises beyond the earth that rises likewise beyond the foregrounded moon, making what amounts to an image that, though impossible astronomically speaking, evokes all of the beautiful and ridiculous finitude of our local gravitational well as it falls through the cosmos. Of the sublime in cinema, this is one of the pinnacles.

But the brutal vastness of space, and the absurd sublimity of both image and film, would soon collapse into conspiracy. The moon landing, taking place the next year in the summer of ‘69, and broadcasted live on national television would become a first-rate example of the Baudrillardian simulation: a selection of the populace just didn’t believe it. The Flat Earth Society, treating NASA as enemy number one, declared that, not only had all Apollo missions had been faked, but that the moon landing itself had been filmed and directed, in a secret NASA soundstage, by none other than Stanley Kubrick. The Shining (1980), so the theory goes, is Kubrick’s cryptic confession to directing the moon hoax, in which the cursed hotel room 237 is the big clue—because the moon is 237,000 miles away, I guess. Meanwhile, in real life, Kubrick had had dealings with NASA because he had shot the just absolutely gorgeous, naturally lit Barry Lyndon (1975) with special light-sensitive camera lenses that NASA had designed for photographing the dark side of the moon.

Earthrise, 1968

The Allostatic Spiral

A less conspiratorial conspiracy playing out on the internet today is whether or not Kubrick dropped acid. For some 2001 is the acid movie. Following walk-outs at early viewings and after Pauline Kael (2017) panned the movie as “ monumentally unimaginative,” the studio panicked and, revamping the ad campaign towards the nascent counter-culture, billed the movie as “the ultimate trip.” Subsequently many felt the need to watch the movie on acid. Surely its creator had gone there also? Michael Pollen has even claimed (2019) that Kubrick underwent LSD therapy when it was the rage in Hollywood in the fifties and sixties, back when acid was legal, had no stigma and pretty much everyone was doing it under the auspices of Psychiatry. But Kubrick himself remained equivocal and denied use:

I have to say that it was never meant to represent an acid trip. On the other hand a connection does exist. An acid trip is probably similar to the kind of mind-boggling experience that might occur at the moment of encountering extraterrestrial intelligence. I’ve been put off experimenting with LSD because I don’t like what seems to happen to people who try it (Turn Me On Dead Man, 2013).

We may speculate that what seems to happen to certain people on acid is that following their encounter with the alien, they cannot merely return. Perhaps Kubrick, as the supreme auteur, was afraid of this loss of control? If your habitual experience is, as the psychologist liked to say, a stream of consciousness, a river into which you cannot step twice, then acid makes this stream a cataract. Once you return to a normal volume of flow, you may find yourself considerably down river. While acid is technically non-addictive, there are, nevertheless, certain rare persons who are addicted to acid. They are addicted not to the substance, but to the experience; they are addicted precisely to the cataract, to overwhelm. The specific name for this in literature is allostatic overload, but for our purposes and following Dominique Scarfone, we will call this the allostatic spiral.

Scarfone (2025), in an as-of-yet unpublished paper given at the Allison White institute in summer of 2025 called The Sexual Drive for Power spoke of the passion for more and more that characterizes a certain kind of sexual excess. As opposed to the feedback loop of homeostasis, the allostatic spiral is a feed-forwards loop and a self-amplification, driven from one satisfaction to the next, with desire increasing with each spiraling pass.

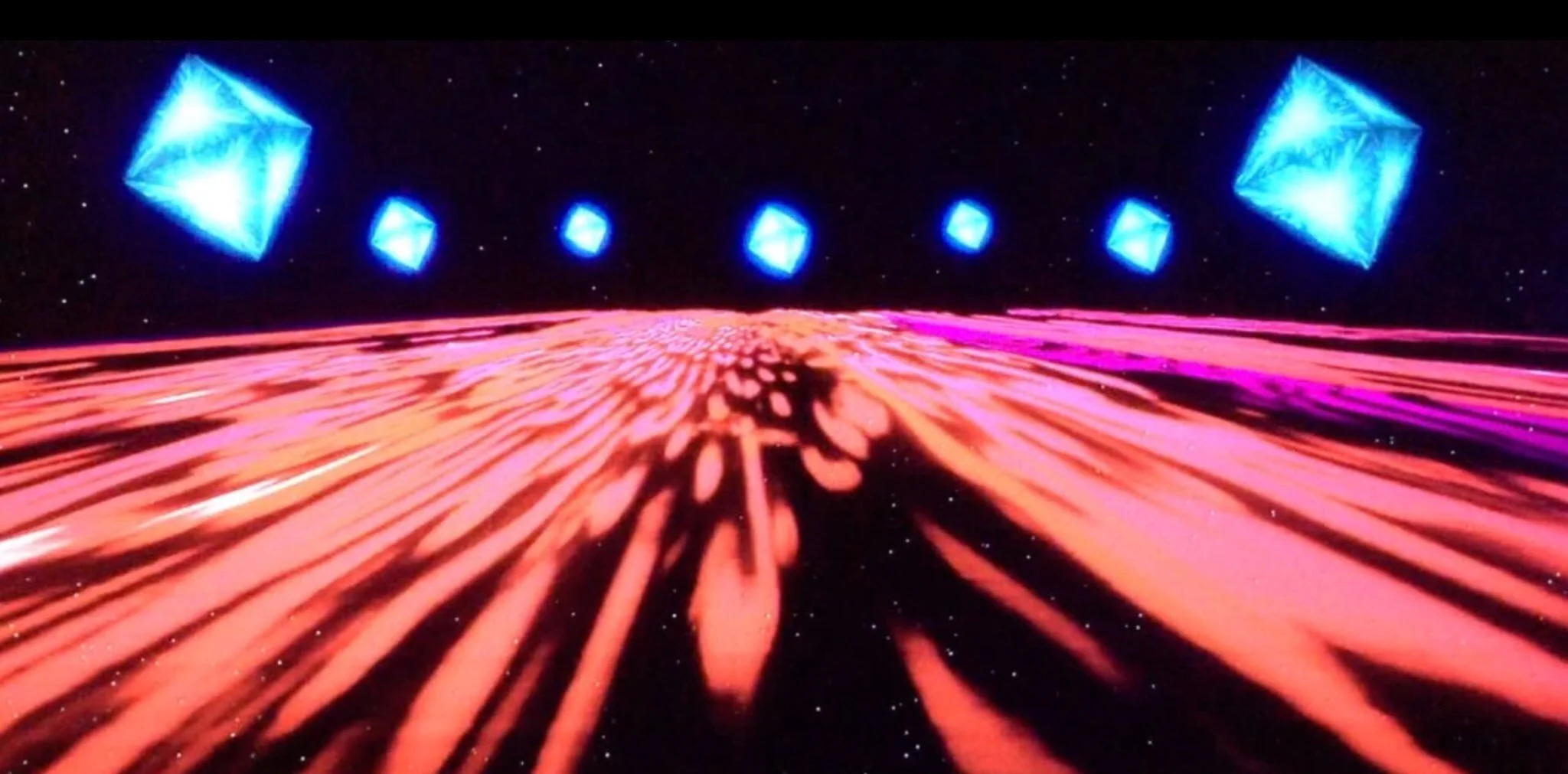

This is the spiraling arc of 2001. Once astronaut Dave Bowman unplugs HAL9000, the malignant and infallible AI pilot of the spaceship (almost as if he were unplugging God?), he follows the alien monolith into the abyss of space. Passing beyond the limit, he falls into the long chaotic “stargate” scene that famously overwhelmed audiences (it overwhelmed me when I saw it at the Film Forum in 2018). Psychedelic space is transposed upon existential space; the blackness of space flashes to vibrant color; where once Dave had been journeying outwards, now he journeys within. The infinite chasm of the galaxy becomes the projected space of his own dreamscape—and from which, ultimately, he cannot return without transformation.

Stargate sequence in 2001

Sympathy for the Abyss

Is this a new kind of narrative arc? Where before the arc of no return would be otherwise known as tragedy, or the tragic return, such as Oedipus Rex, this new arc, taking 2001 as the pre-eminent example, forecloses any naive return; the arc becomes a spiral. This spiral arc of no return is prefigured in a number of quintessentially modern variations, perhaps most thoroughly embodied by works such Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (2025), Moby-Dick (1983) and Thomas Man’s novella Death in Venice (1989). These are works in which the protagonist pursues an object of desire into a state of overwhelm and finally abysmal disaster.

Gustave von Aschenbach, the hapless protagonist of Death in Venice, though he has spent a writing career renouncing “the sympathy of the abyss” (p. 13), he nevertheless indulges in “an impulse towards flight,” (p. 6) and, vacationing in Venice, becomes obsessed with a beautiful teenage boy and subsequently careens headlong into feverish heights of overwhelming erotic feeling that culminate in his own death; the very abyss he had so faithfully avoided turns out to be what he longs for and ends up hurtling into.

Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) evokes both the spiral and the abyss with its vision of Jimmy Stewart’s spinning head, and his mad obsession with the woman of his dreams. The dream of falling and the dream woman finally converge with the falling death of the hapless Kim Novak. This movie, perhaps more than any other, produces the dizzying force of the allostatic spiral in all of its unstoppable agony and bliss.

detail of Vertigo poster

The Arc of No Return

These days the horror genre obviously holds the monopoly on the arc of no return, take Carrie (1976) as prototype. The exceptional science-fiction horror film Alien (1979), is basically Moby-Dick in space, where the white whale becomes the superweapon xenomorph. Astrophysics has immortalized the arc of no return as the event horizon, that point beyond which light cannot escape the black hole; Event Horizon (1997), a rather excruciating space-horror movie, takes this event all too literally.

But the arc of no return does not only imply that everyone dies—although it can mean that—it is rather a transformation through trauma—even a kind of traumatophilia, in which the death drive and eros are indistinguishable. For Jean Laplanche (1976), the death drive is not beyond the pleasure principle but rather is the pleasure principle in its most radical dimension. Aschenbach’s desire for the abyss makes an excellent example of this radicality.

This is essentially the idea and phenomenon that Dominique Scarfone (2025) is attempting to develop and complicate with his exploration of the allostatic spiral. Nor is he alone in this endeavor. Avgi Saketopoulou, his collogue and occasional co-writer, has likewise produced a variety of notions by which to think this special condition, in particular the overlapping concepts of limit consent, overwhelm and traumatophilia. In her paper The Draw to Overwhelm (2019), Saketopoulou lays out two economic regimes of sexuality, following Freud’s speculations in The Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), in which on the one hand there is the sexual instinct, beginning after puberty, bent on binding, synthesis and the release of tension, and on the other there is the sexual drive, the domain of infantile sexuality as such, driven to unbinding, escalation and the pleasurable increase of tension (Saketopoulou, p. 145). “Overwhelm occurs when the sexual drive escalates with negligible interruption or modulation. Excitation stockpiles beyond the pleasure principle, into pleasure that is suffered. If this escalating excitation becomes so excessive that it reaches past the brink, overwhelm can threaten the ego’s coherence” (p. 150).

Aschenbach’s impulse towards flight, in Death in Venice, not to mention Dave’s flight beyond the limit in 2001, is, I think, not only the impulse towards rising excitation, but also precisely an impulse towards unbinding the ego and overthrowing habitual narratives, the narratives of naive return.

For some reason (🤔) the year of our lord 2018 was a bumper year for just this kind of narrative arc. Aniara, a Swedish sci-fi film, based on a 1956 poem of the same name, lead the charge in its bleak outlook and expresses the arc of no return in the most literal of terms. A cosmic cruise ship, ferrying passengers from a destroyed earth to a recently colonized Mars, malfunctions and, its course permanently altered, journeys indefinitely without destination into the emptiness of the cosmos; existential panic ensues, weird sex cults are formed; spoiler alert: they will not be rescued. Likewise released that year was Claire Denis’s very good High Life, starring Juliet Binoche, Robert Pattinson and Andre 3000; it is a similar story regarding a spaceship full of juvenile delinquents sent, as an experiment, to fly into a black hole. There was also Annihilation, starring Natalie Portman, a not-that-great adaptation of the excellent Jeff Vandemeer novel of the same name (2014), following a group of scientists as they pass beyond the known world in the exploration of the mysterious site of ecological disaster Area X. And lastly Gaspar Noé’s Climax, the story of a dance troupe, convening at an abandoned high-school, and where the punch has been spiked, of course, with acid—madness and terror ensue.

Late to this party—but very much belonging to it—there is the horror-thriller Underwater (2020) starring Kristen Stewart. This movie is exceptional, tightly constructed, scary but not-too-scary, and all the time gorgeously lit. Like if Alien was high on 2C-B and set at the bottom of the ocean.

These movies are not for everyone, just FYI.

The Arc of the Same

The basic feature of the arc of no return—that the main character, or characters, do not and cannot return to normal—may be contrasted by its opposite and far more common narrative type, which is, you guessed it, a complete return to normal. Interstellar (2014), Christopher Nolan’s homage to 2001, betrays its own stunted imagination by allowing Matthew McConaughey, even after falling into a black hole, a complete return to the cocky authority of Matthew McConaughey. Unlike Dave in 2001, who suffers radical break-down and total transformation, Matthew McConaughey is allowed to go on being exactly himself. The Martian (2015) staring Matt Damon, is this same old story: after a harrowing journey of survival in the harsh Martian surround, plucky Matt Damon returns to the green earth and drinks a coffee. The viewer is comforted to know that, though Mars may be hell, Matt Damon, and Starbucks last forever.

These are complacent movies for a complacent age; but really, it’s an old plot and we can find its like everywhere from The Book of Job, to Homer’s Odyssey, to Robinson Crusoe, to Wizard of Oz. It is no wonder that Nolan’s upcoming release is an adaptation of The Odyssey, starring, surprise! the everyman Matt Damon. Following Francis Fukayama’s 1992 thesis (1999) that, with the advent of global capitalism, history has finally come to an end and we can just go on consuming Coca-Cola and Taco Bell without fear of cataclysm, we will call this all-too-common plot type—embodied by the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Tom Cruise movies and nearly every sitcom—the arc of the same.

Matthew McConaughey awakes from a nightmare: “who is my hero?” he asks. Then he remembers, his hero is Matthew McConaughey.

The Death of God

To reiterate: in the arc of no return, the ship has no pilot, or, like HAL9000, or Captain Ahab, the pilot is inimical; in the arc of the same the pilot is Matthew McConaughey. This clues us into a basic historical feature of the arc of no return, and what separates it finally from tragedy: it is a plot type that arrives following upon the death of god. Existential angst, going off the charts in the post-war era, is an acute expression of both helplessness, that most fundamental of human emotions, and overwhelm. When the parent neglects to rescue the infant from their own screams, or if the parent overstimulates the child (Saketopoulou, 2019), the infant enters the allostatic spiral and through the compounding effects of both helplessness and overwhelm they face mental breakdown after which overwhelm forever after becomes the expedient solution to mental distress.

I think this has something to do with the primordial feeling state those astronauts are registering when they view the earth from a tin can hanging in the void. Known as the overview effect, this is a kind of breakdown that one suffers upon viewing the planet from outside of it. The most famous subject of this peculiar breakdown was William Shatner, after his own Jeff Bezos manned orbital mission. Shatner wept upon return to earth: “I hope I never recover from this.”

Obviously and as I’ve said before, this is an historical viewpoint. One that has been afforded by our recent rocket technology, but one also that is existential; the postwar, modern realization that there is very little that separates us from the void. Nuclear arms, climate change, and societal collapse all threaten what little solace remains. That the arc of no return figures so highly in the movies of 2018, midway through the first Trump administration, is an expression of this same helplessness, together with a good dose of overwhelm. The internet is acid, the future is being foreclosed and the entire culture is in an allostatic spiral. Where we once could trust that god or king, or our parents would save us, would steer the ship clear of danger, now we are beginning to realize that no one is steering this space ship.

This is probably what the flat-earth conspiracist (not to mention the religious person) cannot finally accept and so must disavow; there must be someone in charge! Who cares if they are malevolent! So the infinite void of space is just a government soundstage, directed by Stanley Kubrick.

passing beyond the limit

Note: being swept down the river of consciousness is probably not quite the right metaphor, for it implies that something remains static, whereas, in real life nothing is static and everything is ceaselessly in flux. This is like in the Borges essay: “it is a tiger that devours me, but I am the tiger.” In William James’ conception the stream of consciousness is everything, it is life itself, or as he calls it, the world of pure experience.

Works cited

Anderson, P. (Director). (1997) Event Horizon [Film]. Paramount Pictures

Denis, C. (Director). (2018) High Life [Film]. A24

De Palma, B. (Director). (1976) Carrie [Film]. United Artists

Freud, S. (1905) Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 7:123-246

Fukuyama, F. (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press

Garland, A. (Director). (2018) Annihilation [Film]. Skydance

Hitchcock, A. (Director). (1958). Vertigo [Film]. Paramount.

Kael, P. (2017) Pauline Kael on ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/movies/pauline-kael-on-2001-a-space-odyssey/

Kågerman, P. and Lilja, H. (Directors) Aniara [Film]. Meta Film Stockholm

Kubrick, S. (Director). (1968) 2001: A Space Odyssey [Film]. MGM

Kubrick, S. (Director). (1975) Barry Lyndon [Film]. Warner Bros.

Kubrick, S. (Director). (1980) The Shining [Film]. MGM

Laplanche, J. (1976) Life and Death in Psycho-Analysis. (Trans J. Mehlman). Johns Hopkins U Press

Mann, T. (1989) Death in Venice. Vintage international

Martinson, H. (1999) Aniara. (Trans. Klass, S. and Sjöberg L.). Story Line Press

Melville, H. (1983) Moby Dick or, The Whale. University of California Press

Noe, G. (Director) (2018) Climax [Film]. Wild Bunch

Nolan, C. (Director) (2014) Interstellar [Film]. Paramount Pictures

Nolan, C. (Director) (2026) The Odessey [Film]. Universal Pictures

Pollan, M. (2019). How to change your mind: The new science of psychedelics. Penguin Books.

Saketopoulou, A. (2019) The Draw to Overwhelm: Consent, Risk, and the Retranslation of Enigma. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 67:133-167

Scarfone, D. (2025), The Sexual Drive for Power. The Passion For Ever More. Public talk given at the Alanson White Institute on 04.04.25.

Scott, R. (Director). (1979) Alien [Film]. 20th Century Fox

Scott, R. (Director). (2015) The Martian [Film]. 20th Century Fox

Shatner, W. (2022) Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder. Atria Books

Shelley, M. (2025) Frankenstein. Vintage Classics

Turn Me On Dead Man, 2013, Trippy Films: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) https://turnmeondeadman.com/trippy-films-2001-a-space-odyssey-1968/

Vandermeer, J. (2014) Annihilation. Macmillan