Iridescent Strange Attractor

When you keep doing compulsively what you had vowed never to do again, even though, or especially though, it causes you great harm, then you know that you’re in the field of a repetition—and probably a very old one. Freud described the repetition compulsion as “some daemonic power,” because it seems to act of its own accord, without your express command. So repetition tends to get a bad rap. We repeat what we can’t remember. This belies the fact that we all live in repetition; that our lives are made out of various repetitions in various time signatures—yearly, daily, hourly, moment to moment—some more conscious than others. If I did not write daily, I would not be a writer. Repetition is not only compulsory, but is the medium, the carrier wave of daily life.

Terence McKenna built a whole metaphysics on the binary novelty and habit and I think that’s not a bad way to think about the drives, those psychic forces that determine our behavior. On the one hand there is habit, the instinct of self-preservation, binding, organization, and synthesis. And on the other hand there is novelty: the drive towards unbinding, dissolution, disorganization and nirvana. Novelty tends to warp habit, whether we like it or not. In the last instance the transformation of death is the greatest novelty and oldest of habits, mors immortalis; the pure abstraction of movement—as Marx liked to say.

Whereas self-preservation longs for the safety of pure repetition—Tradition, to use the parlance of T.S. Eliot and Trad Caths—the unrelenting forces of novelty, of continuous flux, bend this repetition into a loop-de-loop, a bent spiral; or pulsing helix. Tradition is revealed—hopefully—as a fantasy cast up out of architecture and calendars and the shredded cyclic poem that is language. The spiraling movement of novelty and habit are nested inside one another to the point where it becomes difficult to disentangle one from the other. The repetition compulsion, when it is daemonic, can be thought of as the earliest form of an attempt to master the shear novelty of infantile experience, even while it can tend to produce, later on, a novelty that disrupts the mature repetitions of the habitual ego. The novelty of childhood, of an impulse that is far older than religion, returns on the carrier wave of a habit that lies outside the bounds of thought—or architecture for that matter.

McKenna’s big idea was that we are all being pulled into the future by a novelty sink that he called the transcendental object at the end of time. The upheavals in the world today are but the cataracts of novelty as we near the zero-point. While I don’t mind the notion that we are being pulled into an unknowable future, I get bored by the apocalypse. It is also obvious, to me, that the singularity that McKenna foresaw is something that already happened, in his own cosmogony, way back when language was born from the mushroom in the mind of the stoned ape.

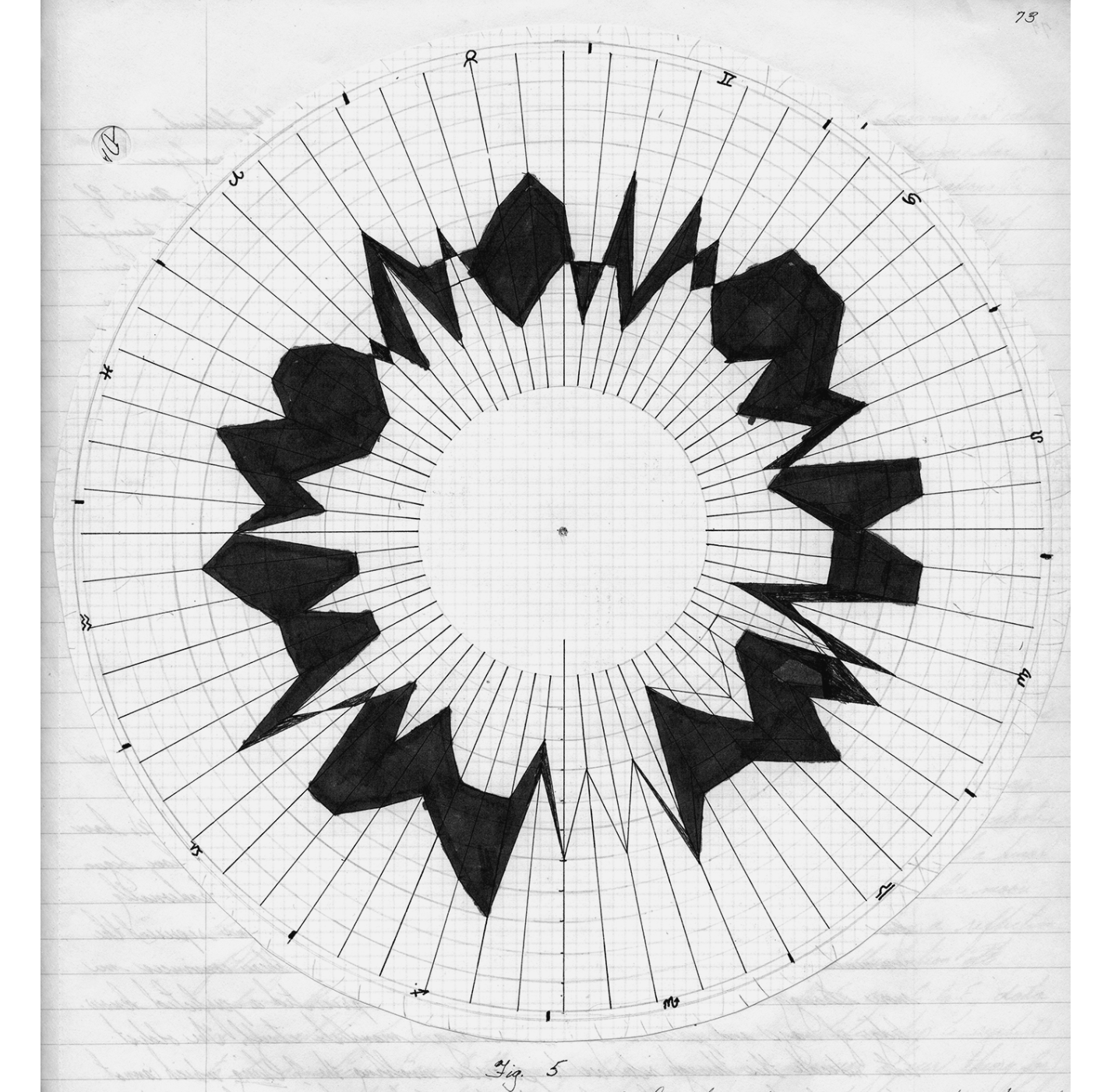

This is like an epic sci-fi version of Freud’s view that species development is repeated by individual development (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny); like if the novelty of childhood was cast into the future from where it produces the iridescent strange attractor; the eddies of which we encounter day to day, in the form of unconscious desire.

Timewave Zero, Terence McKenna

Abstract Painting no. 95, 1939, Lawren Harris