The Transcendental Android

Hayao Miyazaki awakened my young mind at age eleven when I watched Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Having been steeped in Disney cartoons, I was shocked: I didn’t know that an animated movie could be like this. In retrospect I think this was the moment when modernity touched down in my heart.

Rarely do we see the transformative power of sublimation better than in the Japanese science-fiction of the post-war era. Nuclear destruction and defeat has been transduced into an entire vital genre. The American production of inferno and total war is personified by the giant kaiju monsters that dominated 1950s Japanese cinema, such as Godzilla, but that reappear again and again in manga and anime, as in Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995). Nausicaä tends towards the literal in that the bomb is made into a nuclear humanoid kaiju called the God Warrior. A representation of the human as prosthetic god in which nuclear holocaust is his prosthesis, the God Warrior, like many kaiju, is a version of Frankenstein’s monster; a creature of pure artifice, inimical to humanity.

The God Warriors, Nausicaa, 1984

These large fantastical creatures hold sway over our imagination because of our own inborn proclivity to project anthropoid phantasms onto the undulating surface of humankind. François Laruelle has named these projections the transcendental androids. They are a mixture of the human with an idea, more particularly a philosophical decision, as in Aristotle’s description of the human as a political animal, or when the bible declares that humankind is fallen, sinful and evil. One may only examine a thousand years of medieval European society to see what such a “sinful” android hath wrought: mass illiteracy, rampant disease, normalized domestic abuse, cruel corporal punishments and very low to non-existant personal hygiene: such are the manifest virtues of Christendom.

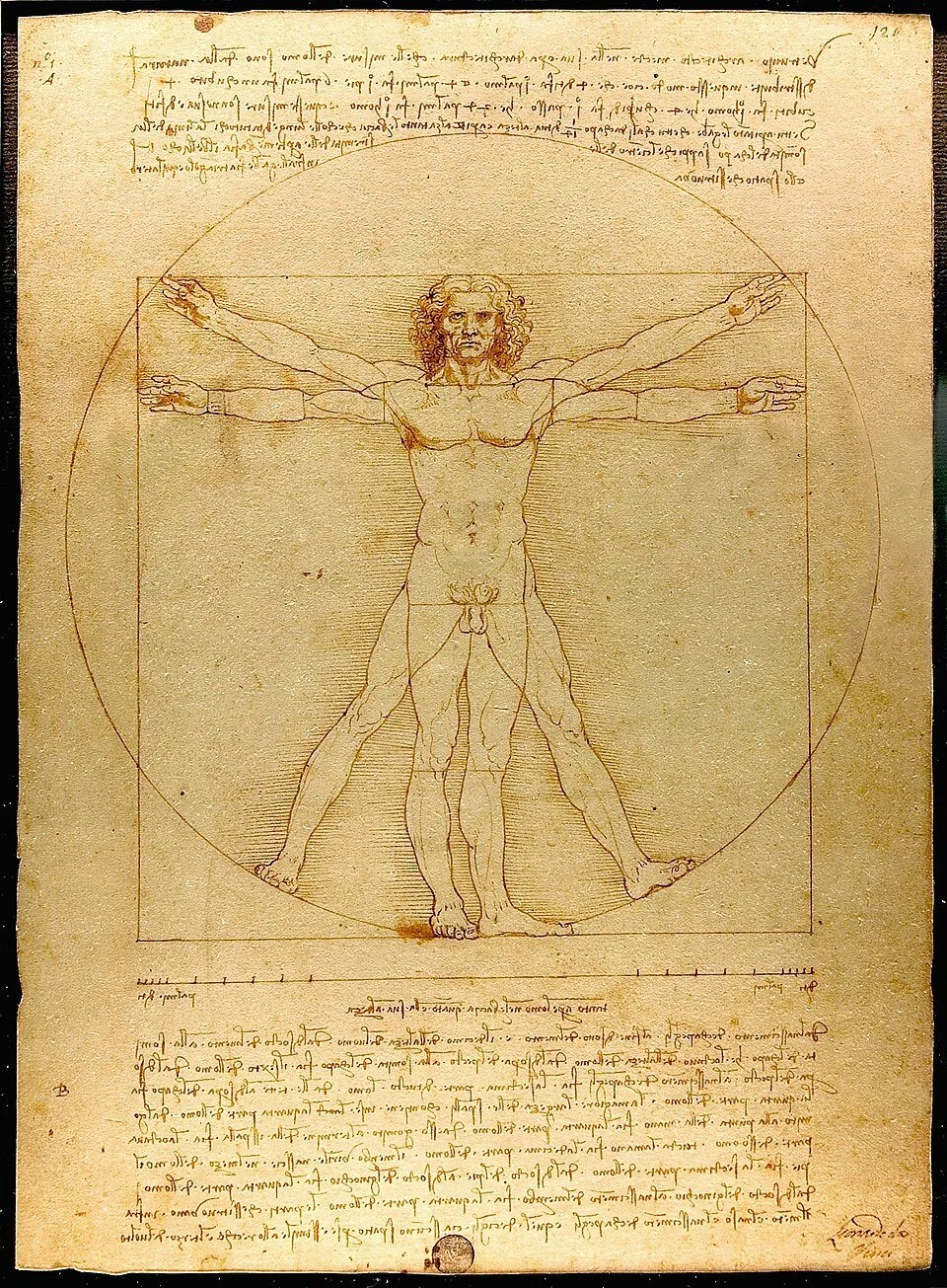

The transcendental android is an android, because they are an invention. They are transcendental because the human is combined with ideal notions such as material, spirit, ability, language, desire, existence and so on. Laruelle: “These are fictional beings responsible for populating the desert of anthropological screens, shadows projected on the steep wall of Ideas, inhabitants of Ideal caves.” The transcendental android is not so different than those human figures cast upon the sky in the form of constellations. They are like the kaiju in that they scale to disproportionate size in as much as people believe in them. They become autonomous entities in as much as they determine human perception and behavior. There is perhaps no more caustic nor more catastrophic transcendental android than that of the androcentric android: the human defined as Man.

Vitruvian Man, 1490, Leonardo da Vinci’s ideal proportions of the androcentric android

In Laruelle’s vision, on the contrary, the real human is a stranger, radically immanent, unknown and unknowable; prior to history, outside of philosophy, and totally indifferent to all predicates. It is a working thesis here at spacewhy that one of the means of encountering this stranger (whom we all are) is by ecstatic technique, in any of its many varieties.

Today the cutting-edge transcendental android walking the land is that of the algorithmic human, or the human-as-computer. We can find traces of this android everywhere from machinic visions of abnormal psychology as chemical imbalance in cognitive behavioral science—where the human brain, like a computer, is an algorithmic system of chemical inputs and outputs; or at the Apple store in which the body is a mere appendage to the iPhone; or in the contemporary discourse on consciousness and sentience in the field of AI, as when Sam Altman declares that a human, like a large language model, is a stochastic parrot, where the output is stultified robotic text.

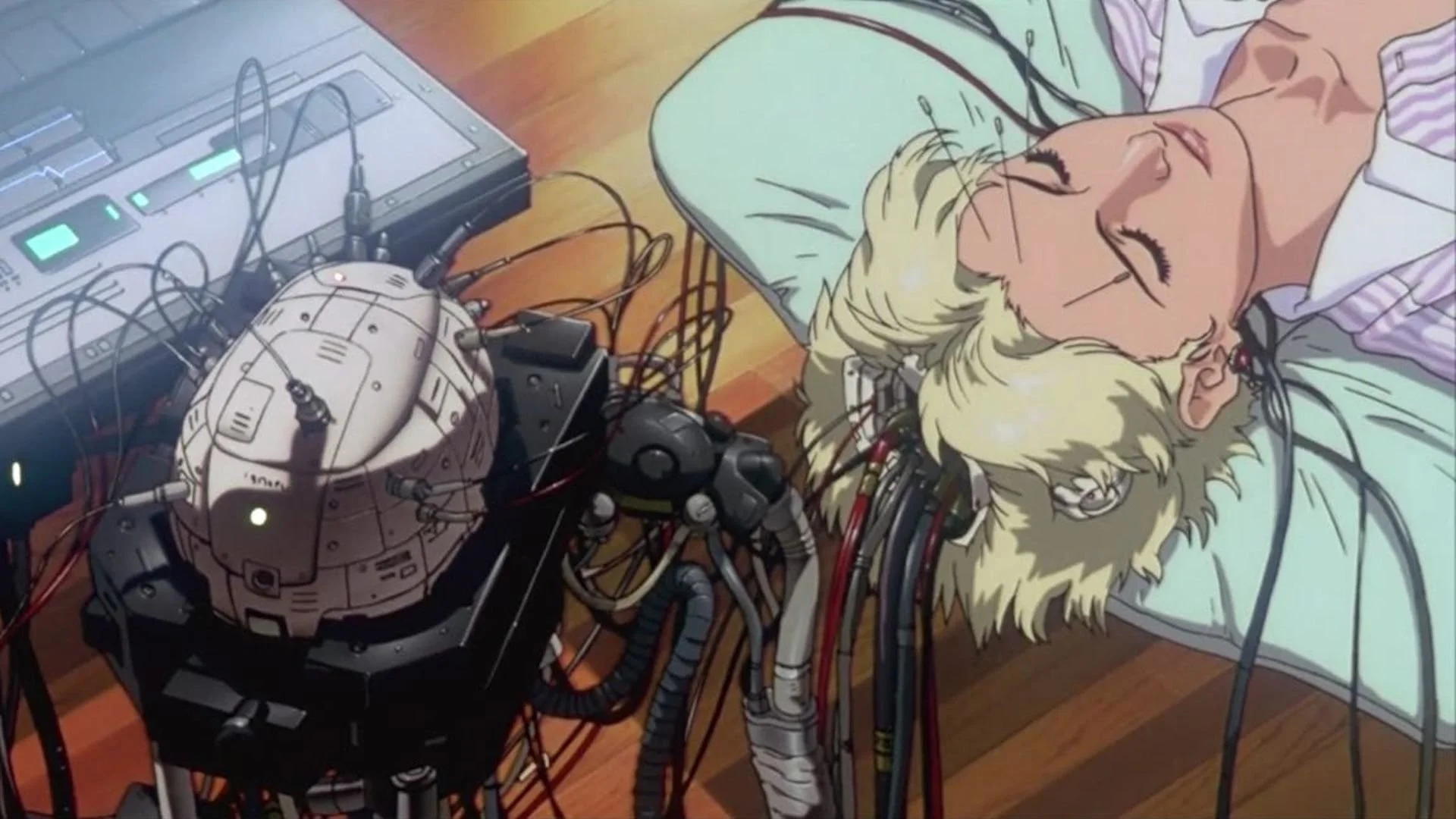

While this psycho-mythology may function as propaganda that attempts to mystify the machine and lift it to the dignity of the human voice, it likewise does double duty by reducing the human to the old materialist’s dream of the brain in a vat—a fate the like of which postwar Japanese sci-fi also has no shortage of visions, like, for example, Ghost in the Shell (1995), in which the transcendental android has become an artificial woman.

Ghost in the Shell, 1994

Mermaid, 2015, Malene Reynolds Laugesen