Visionary Revisions: in Psychoanalytic Writing

In the “Discussion” section of Fräulein Elisabeth von R, Case 5 of The Studies on Hysteria (1893), written early in Freud’s career, at the very beginning of his psychotherapy practice, he expresses a degree of bewilderment: “It still strikes me myself as strange that the case histories I write should read like short stories and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of science.”

For better or worse, history would bear this out and raise Freud to the level of literature. The case histories in particular read, to me, like rated R Henry James stories; except that I get bored by Henry James and Freud’s case histories are never boring. We might place Freud’s case work along side James, Conrad, Wharton, Kate Chopin and so on: the literature of psychological realism prevalent in the late Victorian era, except that, of course, Freud’s cases are not fiction but are the transmuted clinical representations of real persons.

Jamieson Webster remarked recently, on a New Books in Psychoanalysis podcast speaking of the case of Dolto, that Freud’s cases are remarkable in that they can seem to be bottomless, that they can be read again and again, revealing new facets with each reading. It is as if Jamieson Webster were as bewildered as Freud was to find that his case work reads like imaginative literature.

Freud speculates further in the Elizabeth von R case, and it is worthwhile to include it here for it would seem to offer an entire program that those analysts who are invested in writing may still find relevant:

I must console myself with the reflection that the nature of the subject is evidently responsible for this, rather than any preference of my own. The fact is that local diagnosis and electrical reactions lead nowhere in the study of hysteria, whereas a detailed description of mental processes such as we are accustomed to find in the works of imaginative writers enables me, with the use of a few psychological formulas, to obtain at least some kind of insight into the course of that affection. Case histories of this kind are intended to be judged like psychiatric ones; they have, however, one advantage over the latter, namely an intimate connection between the story of the patient's sufferings and the symptoms of his illness.

So we have here the case as a narrative description of interiority, written in the style of an imaginative writer, together with the use of psychological formulae that produce a certain kind of insight that, though he had yet to coin the term, we would recognize today as psychoanalytic.

Psychoanalyst Rachel Altstein in her paper Finding Words: How the Process and Products of Psychoanalytic Writing Can Channel the Therapeutic Action of the Very Treatment It Sets Out to Describe (2016) likewise reads this passage in Freud as a testimony to the visionary powers of writing: “implicit in Freud’s observation about therapeutic insight is that revelatory moments in treatment can be gleaned directly from the imaginative component of psychoanalytic writing.”

The bewilderment that Freud experiences in the writing of his case histories is at once an encounter with his own imagination—not to mention his nascent writing ability—and also a peculiar kind of insight that the imagination alone can afford. The stories lack the “serious stamp of science” precisely because of their focus on the imagination, on a fantasy that belongs to the patient and to the analyst. If science is that which seeks to separate the imaginal from reality, then Freud’s new science resides on the other side of this program, in which the imaginal alone is isolated and drawn out in the treatment. But here the imagination is both the object of study, and the means by which to study it.

Freud’s early bafflement at his own imagination was approaching another as-of-yet unnamed concept in his work: that of endopsychic perception. While he first names the concept in a 1897 letter to Fleiss, he will reveal the idea to the public in the Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901):

A large part of the mythological view of the world…is nothing but psychology projected into the external world. The obscure recognition (the endopsychic perception, as it were) of psychical factors and relations in the unconscious is mirrored…in the construction of a supernatural reality, which is destined to be changed back once more by science into the psychology of the unconscious… to transform metaphysics into metapsychology.

To reiterate: endopsychic perception is a species of unconscious perception that produces the artificial projections that are cast outwards upon the external world. But it is also the means by which one may perceive the unconscious through the medium of those same projections—that of religious belief, mythology, delusions, dreams, fears, fantasies and not least of which are the feeling-states produced by the treatment. All of this can be found in analytic listening. What Freud’s case work implies is that his own secondary revision, that is the case write-up, operates along the same vector of unconscious perception, except that in this instance it is Freud’s own visionary projections that illuminate the otherwise occult psychical reality of the patient.

Jamieson Webster, in the same interview from above, has said that the analyst requires a theory of the case for each patient. What I am proposing, by reading into Freud’s own technique, is that this theory of the case is all the more useful the more imaginative it is. Thomas Ogden notes the paradoxical nature of this casework in his paper On Psychoanalytic Writing (2005): “the analytic writer is continually bumping up against a paradoxical truth: analytic experience (which cannot be said or written) must be transformed into ‘fiction’ (an imaginative rendering of an experience in words)”

In the last instance Freud expands his notion of visionary projection until it includes the metapsychology itself—a metapsychology transformed from metaphysics. The various concepts discovered by psychoanalysis, whether repression, libido, the death drive, are literary figments told in the style of science-fiction that nevertheless, like a stethoscope or microscope, offer perceptions upon an otherwise occluded psychic-life; science-fictions that tell the truth.

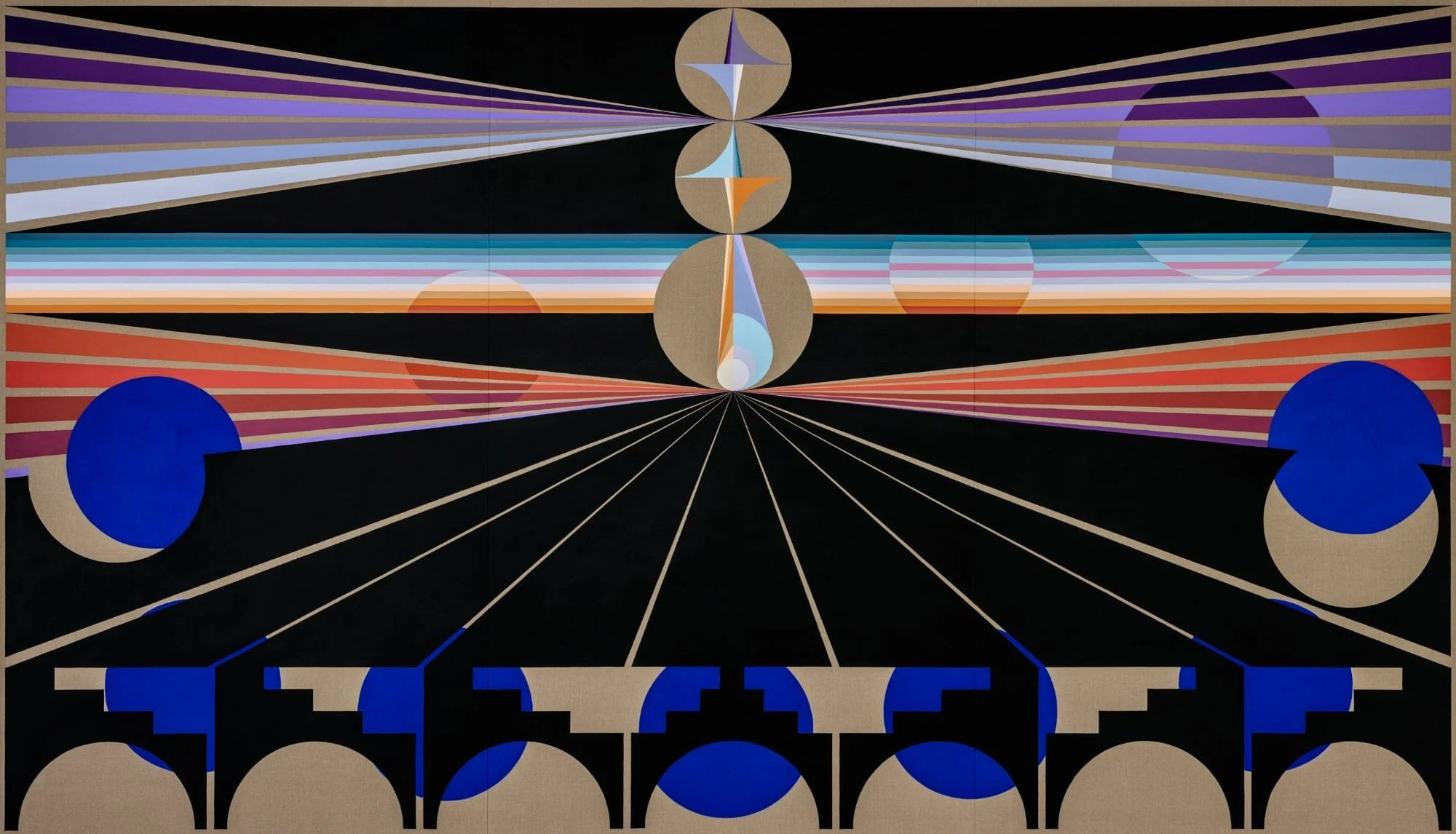

Black Medallion XV (Mama-Quilla), 2023, Eamon Ore-Giron